By: Megan Kilmartin (intern) and Orli Rabin of ThrivingBiome

*Please remember that this post is meant for educational purposes only and any changes made to your diet or treatment/management plan should be discussed with your doctor and other healthcare professionals.

Pregnancy is an exciting time for women, but can also be very confusing. Compounded struggles with gut health, like Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) make this time even more challenging. Advice and tips are being pushed from everywhere, and sifting through all the information can be difficult. Taking a step back to understand what SIBO really is and what that means for your overall health is an important first step. Further, knowing how the hormonal shifts associated with pregnancy affect the gut bacteria and how that relates to SIBO is eye opening and identifies ways that gut health can be supported through nutritious food options rather than intense restrictions such as the low FODMAP diet. Since nutrition restrictions can lead to nutritional deficiencies, the FODMAP diet can be harmful to both the mother’s health and the baby’s development.1 Understanding how to choose foods that meet the heightened needs of the mother while managing SIBO symptoms and supporting the gut microbiome can have a huge impact on the pregnancy journey, the health of the baby, and the development of the baby’s gut microbiome as well. 2

Whether your SIBO diagnosis is new or you have managed it for years, there are healthy, safe ways to support your gut health during pregnancy. Moving away from a low FODMAP diet or other restrictive diets, is possible when you have a better understanding of what foods and ingredients to look for.

Before you begin reading, take a moment and consider what you already know about SIBO, hormone shifts in pregnancy, the low FODMAP diet, and risks of nutritional deficiencies in pregnancy. Then, go ahead and begin reading and see if you learn anything new.

SIBO is a disease characterized by the excessive growth of bacteria in the small intestine. Specifically, SIBO is known to be present when the bacterial population in the small intestines exceeds 105–106 organisms/mL. 3 The type of overgrown bacteria impact the symptoms associated with SIBO, meaning an overgrowth of gut flora that metabolizes carbohydrates into gas and short chain fatty acids is likely to cause bloating without diarrhea while other gut bacteria may metabolize bile salts into insoluble or unconjugated compounds that can cause bile acid diarrhea or fat malabsorption.3 Other types of microbial flora may create toxins that are damaging to the mucosa and inhibit absorption. Understanding the type of bacterial overgrowth associated with the SIBO diagnosis guides treatment and management options as the type of flora will influence the body’s presented symptoms.3 As mentioned, these adverse effects are not limited to symptoms, but also damage the intestinal lining affecting nutrient absorption, leading to malabsorption and reduced integrity of the lining. Individuals with SIBO frequently experience unintentional weight loss, nutritional deficiencies, and develop diarrhea or constipation because of the inability of the intestines to function properly. 3

SIBO can be developed because of reduced secretion of gastric acid and dysmotility within the small intestine. Gastric acid prevents the growth of bacteria ingested, and reduced secretion can lead to proliferation of the bacteria in the small intestine.3 Dysmotility of the small intestine prevents the natural flow of contents along the digestive tract, which promotes bacterial growth and accumulation in the intestines.3

SIBO is becoming more prevalent, which could be in part due to improved access to testing, making diagnosing the condition more achievable.3 Traditionally, SIBO breath tests measure only two gases - hydrogen and methane - after drinking a sugar solution containing glucose or lactulose. Newer, more advanced testing identifies a third gas: hydrogen sulfide, which is typically associated with bloating, loose stools, and abdominal pain.4 Trio-Smart is the test we use in practice to measure all three gases - hydrogen, methane, and hydrogen sulfide, all in one panel.4 The substrate used is lactulose and the testing process can be done at home with a collection of ten total breath samples over several hours.4 This approach is more comprehensive, allowing for a more accurate identification of different SIBO subtypes, which is especially important for cases where SIBO could go undetected with traditional testing methods. In any test, when these gases levels are elevated, bacterial overgrowth in the gut is indicated and understanding the difference between the gases can help determine the proper treatment plan. 3

While testing has become more advanced and accurate, understanding why particular populations are more at risk for SIBO is also important to help design a more individualized treatment plan. Women, for example, have higher reported cases of SIBO than men, likely in relation to the increased prevalence of women to have Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS).3 The level of women’s sex hormones influence microbiota composition and they have a higher visceral sensitivity that suggests dysfunction in the gut-brain axis, which increases likelihood of IBS development. 3,5 Hormonal fluctuations that women experience during the menstrual cycle, menopause, and pregnancy affects the type of flora present in the gut and can disrupt clearing of the small intestine, which creates an environment for bacterial overgrowth to thrive. 5 In a similar way, the microbiota in the gut can modulate the levels of systemic hormones, which disrupt proper reabsorption of estrogen, which affects the hormonal balance in the body.5 That disbalance between the body’s hormones and the microbiota in the gut can contribute to SIBO development. In some cases, estrogen upregulates the tight junction proteins that strengthen the gut barrier and maintains integrity of the gut lining, so estrogen fluctuation allows for greater bacterial overgrowth.5 Progesterone can cause relaxation of smooth muscle tissue, leading to slowed gastrointestinal motility and promoting overgrowth in the gut.5 This largely occurs during pregnancy and the luteal phase of the period, which are times when progesterone levels are elevated.5

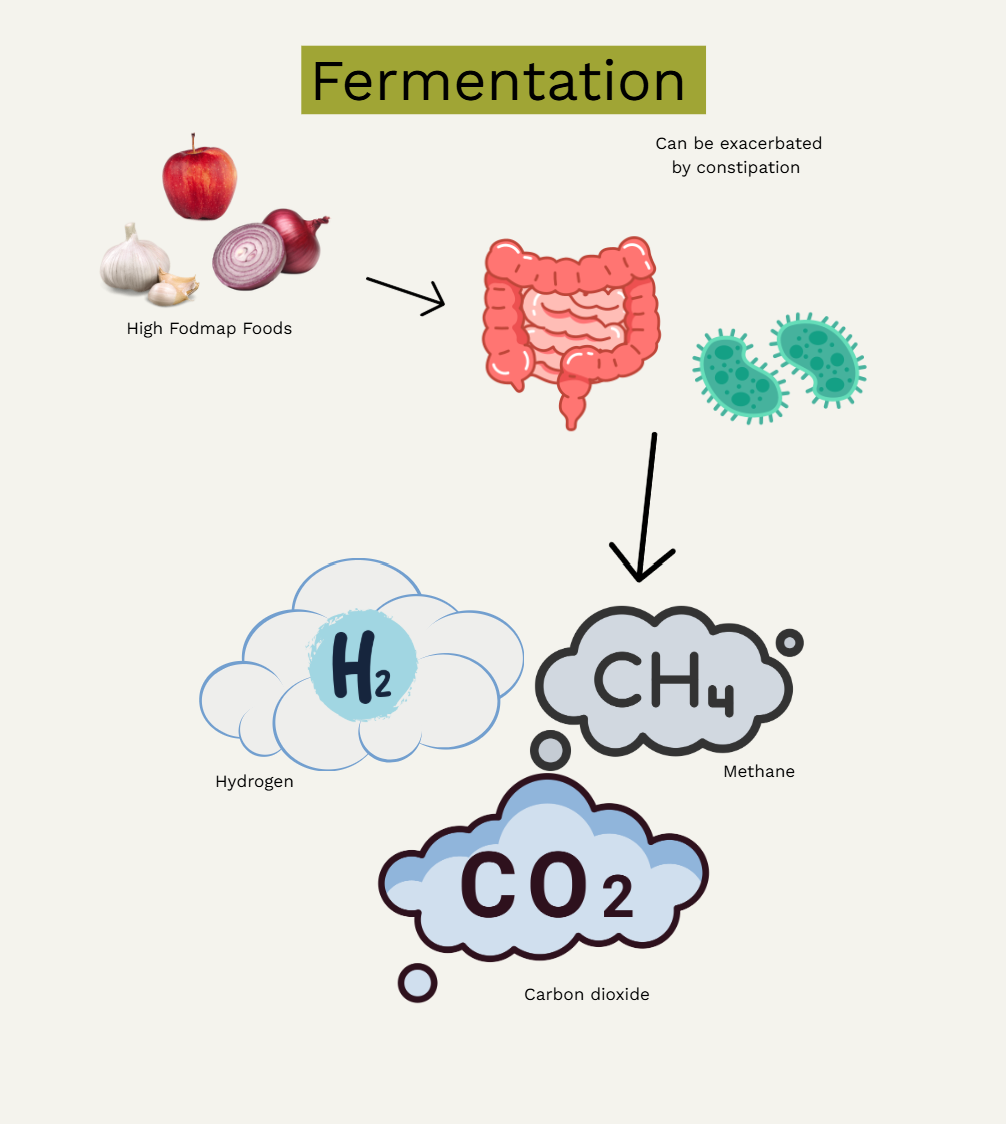

In the conventional medical setting, SIBO is commonly managed with a low fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAP) diet as these sugars are not easily absorbed in the small intestine.1 The low FODMAP diet works to reduce symptoms of SIBO due to a few potential mechanisms of action: osmotic activity and fermentation. The short-chain carbohydrates are poorly absorbed in the small intestine so draw water into the intestinal lumen via osmosis, which can lead to distention and symptoms such as bloating and diarrhea. Once they reach the large intestine, they are rapidly fermented by gut bacteria, producing gases like hydrogen, methane, and carbon dioxide. The fermentation process causes further intestinal stretching and can contribute to abdominal pain, cramping, and altered bowel habits, especially in those with visceral hypersensitivity, such as those with IBS. These mechanisms explain why the low FOMDAP diet improves these gastrointestinal symptoms for many individuals.

The diet restricts higher FODMAP foods, including many fruits, vegetables, grains, legumes, and dairy because consumption of these can create digestive distress like cramping, bloating, diarrhea/constipation, and gas.1 The low FODMAP diet is a three-step elimination diet with the first step being eliminating high FODMAP foods.1 Eliminated foods typically include wheat based products, beans, apples, cherries, peaches, artichokes, onions, and garlic.1 Individuals are advised to base meals around lower FODMAP foods instead, such as eggs and meats, cheeses like brie, cheddar, and feta, almond milk, rice, oats, quinoa, eggplant, zucchini, tomatoes, potatoes, grapes, oranges, strawberries, and blueberries.1 Recommendations state the elimination step of the diet should be two to six weeks to allow reduction of SIBO symptoms and to normalize levels of bacteria in the intestine.1 The second step is to reintroduce the high FODMAP foods one at a time to identify which foods cause symptoms.1 The third step is removing these trigger foods from the diet long term (or at least avoiding them) and resuming a normal diet again.1

The restrictive nature of the low FODMAP diet poses many concerns regarding overall and long term health. The diet should be implemented under direct and close guidance of professionals who understand the potential risks associated with the restrictive diet to avoid potential complications.6 When implementing this diet, traditional providers may not provide the necessary support to prevent nutritional deficiencies or unwanted weight loss.6 Additionally, the restriction of FODMAPs such as fructans and galacto-oligosacchardies can reduce beneficial bacteria in the gut, such as Bifidobacteria, which is already found to be lower in individuals with gastrointestinal diseases. 6 Following the strict low FOMDAP diet may also decrease useful butyrate-producing bacteria and increase bacteria that break down the gut’s protective mucus layer. 6 While the long-term effects are unclear, these changes raise concerns, especially since no studies have looked at what happens to the microbiome after FODMAPs are reintroduced.6 Lastly, individuals with gastrointestinal diseases and/ or other GI related conditions could be at higher risk for disordered eating behaviors due to the strict dietary monitoring these conditions usually require.6 Research shows that long-term implementation of the low FODMAP diet can lead to food aversions, anxiety around eating, and social avoidance. Some may even develop traits associated with orthorexia nervosa, which is an obsessive focus on food quality and health outcomes. These behaviors can have a negative impact on both physical and mental health.6

Given the complexity of managing SIBO through dietary restriction and the potential risks posed to overall health and nutritional status, these concerns become even more significant during pregnancy, a time when nutrient demands are elevated and both maternal and fetal well-being must be prioritized.

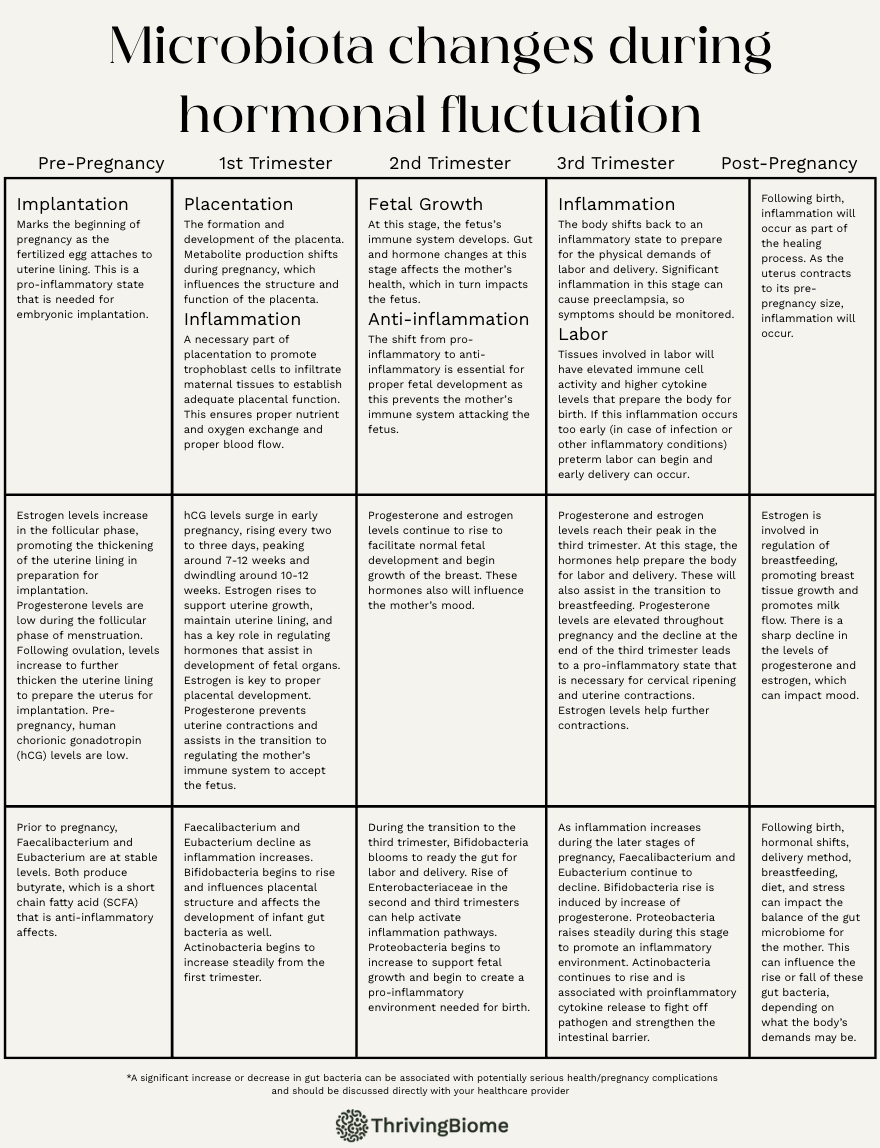

In pregnancy, the hormonal fluctuations impact the gut microbiota of the mother, which can affect SIBO symptoms, but is also so important to the development of the baby and preparing the body for birth.

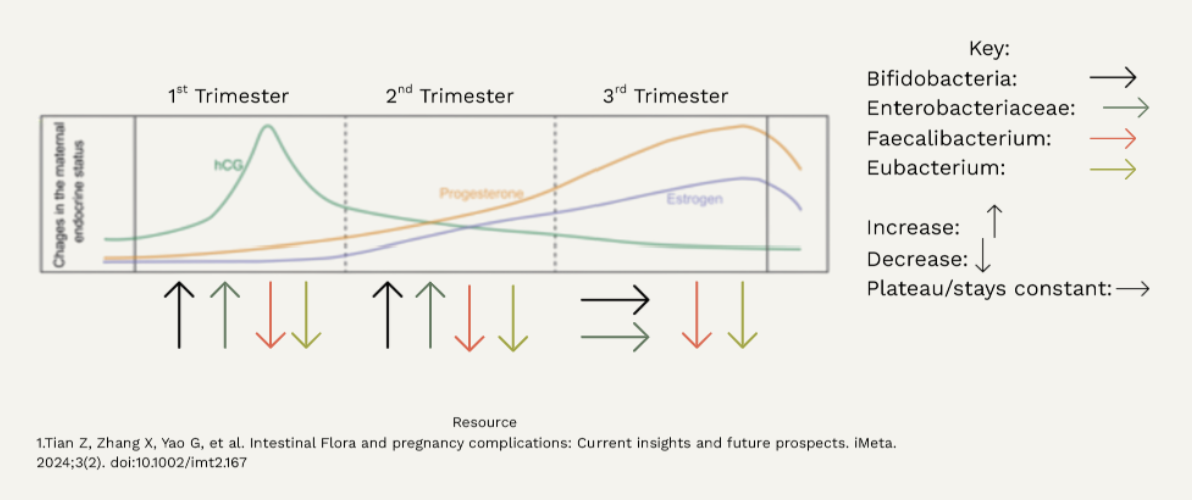

Throughout pregnancy, hormonal fluctuations play a central role in shaping the maternal gut microbiota, creating distinct microbial patterns across each of the three trimesters.7 Early in pregnancy, rising levels of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), progesterone, and estrogen help support uterine growth and fetal organ development, while also beginning the shift from a pro-inflammatory to an anti-inflammatory state to protect the developing fetus.8,9 During this period, beneficial bacteria like Faecalibacterium and Eubacterium, which are both known for producing butyrate, the anti-inflammatory short-chain fatty acid, begins to decline.7 At the same time, Actionbacteria, including Bifidocabterium, starts to increase.10,11 By the second trimester, this Bifidobacterium bacteria becomes more dominant, preparing the maternal gut for energy storage and supporting fetal growth.10 As estrogen and progesterone continue to rise, they begin to influence mood and metabolism, which can cause mood swings and changes in appetite. Toward the third trimester, Proteobacteria and Enterobacteriaceae increase to foster a pro-inflammatory state that is necessary for labor and delivery. This inflammatory shift is further driven by a drop in progesterone and elevated cytokine levels.12 Postpartum, the sharp decline in estrogen and progesterone impacts microbial diversity, while Faecalibacterium and Eubacterium remain low, and Actionbacteria continues to rise. This highlights the dynamic and intricate relationship between hormones and gut bacteria during pregnancy. See the chart below for more details about the intricate relationship between hormone levels and gut bacteria and how these are connected to each stage of pregnancy.

As seen above, the body goes through a number of changes during pregnancy, and these changes can impact SIBO expression and symptoms. As progesterone rises, digestion naturally slows down, which can increase the risk of bacterial overgrowth in the small intestine.12 Estrogen and progesterone work together to reduce inflammation, strengthen the gut barrier, and make the gut less sensitive to pain and bloating.13 Bacteria like Faecalibacterium and Eubacterium help keep inflammation down, but may decline early in pregnancy while Bifidobacterium increase and offer protective benefits.7 Toward the third trimester, there is a rise in the Proteobacteria and Enterobacteriaceae that can be associated with dysbiosis. However, this doesn’t always mean that symptoms will worsen!15

Many women with SIBO report their symptoms improve during pregnancy. The second trimester is a period of anti-inflammation where the immune system calms down to support the growth of the baby.13 During this time, symptoms such as bloating, fatigue, and gut discomfort may be eased. Hormones also impact how the mother feels because fluctuation can lead to reduced gut sensitivity, calming of the nervous system, and helping the body become more resilient to digestive changes.12 Of course, everyone's body is different, and for some these changes lead to a more balanced gut and less distress even if bacterial overgrowth is still present.7,16 This demonstrates that SIBO can be managed during pregnancy and that the body adapts in powerful, impactful ways.

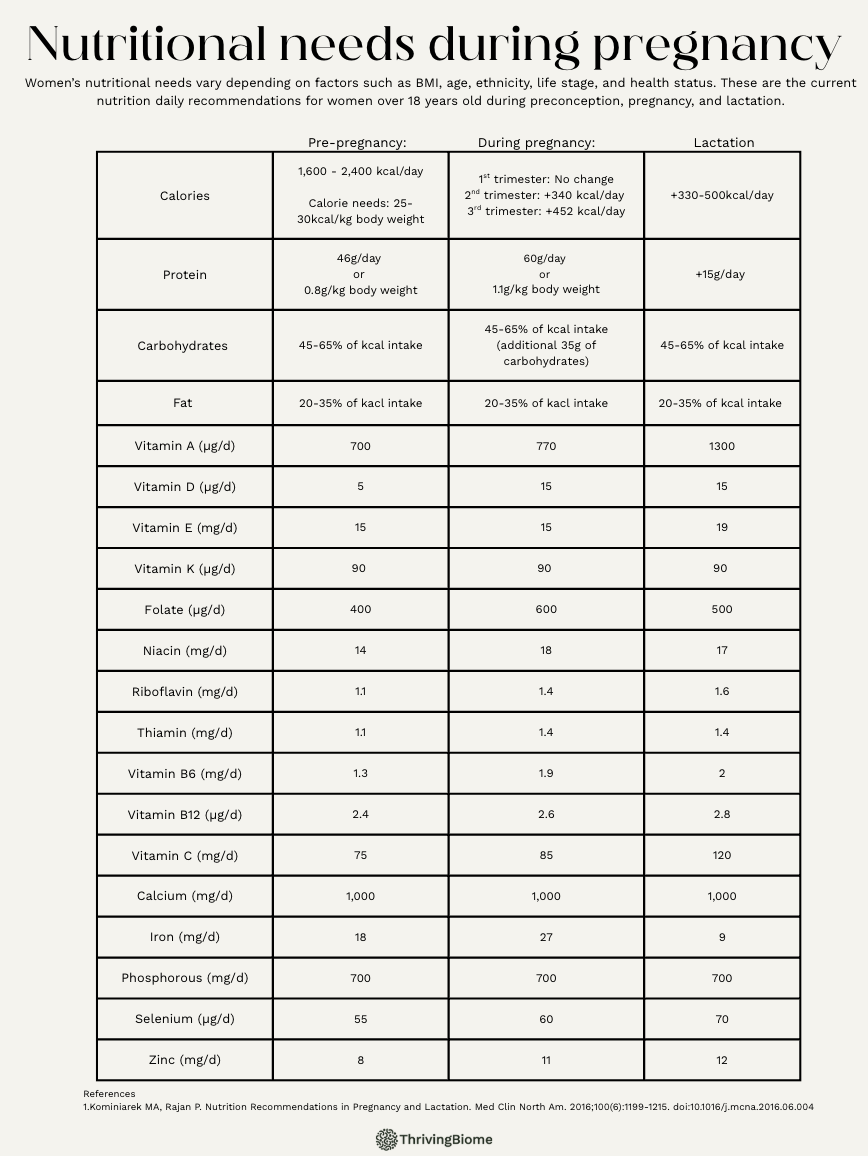

While the low FODMAP diet is recommended for individuals with disorders such as SIBO and IBS, the use of the diet during pregnancy is not. Monash University, the developers of the low FODMAP diet, has stated that limiting or restricting food groups and foods that contain sources of fiber, vitamins, and minerals that are necessary during pregnancy is not recommended or ideal. 2 As pregnant women have increased nutrient demands, restricting these important nutrient sources can increase risk of inadequate intake and lead to impaired fetal growth.2

Managing SIBO while also supporting a pregnancy can seem challenging, but finding a way to do this without food restrictions is important for the nutritional status of the mother and proper development of the fetus. 17 A mother who is deficient in key nutrients increases the risk of a child born with birth defects or other complications. Inadequate intake of calories or protein has been associated with miscarriage, premature birth, and restricted fetal growth. 17 Specific nutrient deficiencies are associated with risks as well. For example, a lack of iodine can lead to stillbirth, intellectual disabilities, and thyroid problems for the child, while a reduced intake of vitamin A can lead to eye and vision dysfunction.17 Vitamin A deficiency is the leading cause of blindness and impaired vision in developing countries where adequate intake of this nutrient is more difficult.17

The B vitamins are a group of essential nutrients that have a critical role in a healthy pregnancy, especially for women with SIBO who may struggle with nutrient absorption. Folate, B9, is crucial for early fetal development and is needed to prevent neural tube defects, which are birth defects of the spinal cord and brain.17 Lack of folate in the diet can lead to spina bifida or anencephaly, which are two forms of neural tube defects and the most common.17 Vitamin B12 works alongside folate in support of DNA synthesis and red blood cell production, and deficiencies in either can increase the risk of birth defects and pregnancy complications.17

Reduced choline intake may affect brain structure and function that could lead to cognitive and behavioral issues later in life. Choline is found in foods such as fish, eggs, broccoli, meat, and dairy products, and is an essential nutrient as the body is unable to produce adequate amounts.17 Vitamin D deficiency has been linked to restricted infant growth, poor bone mineralization, and neonatal hypocalcemia, and is also important to establish and build the immune system.17 Vitamin D levels also need to be maintained post birth if a child is exclusively breastfed to continue proper development.17 Vitamin K deficiencies are less common, but increase risk of miscarriage and early birth while infants will display cognitive impairment, optic atrophy, and complications in bone development.17

Low zinc status can increase the risk of congenital defects and impact cognitive and behavioral development in later life.18 Low birth weight is also common when mothers have a zinc deficiency, which can lead to developmental delays, digestive issues, and increased risk of infection.18 Copper deficiency has been associated with cognitive impairment in infants and connective tissue and cardiovascular defects that could be fatal.17

Today, many foods are fortified with these important nutrients, such as milk fortified with vitamin D or bread and cereal fortified with folate, which makes getting these necessary nutrients easier. Heightened attention to these nutrients is necessary for women with SIBO as trouble absorbing nutrients may exist, affecting nutrient status. Understanding how nutrient needs increase during pregnancy and the potential difficulty absorbing these nutrients due to SIBO will help prevent deficiencies and fetal and infant development. Restricting food groups makes receiving adequate levels of these nutrients more challenging, which is why the low FODMAP diet is not recommended for women with SIBO during pregnancy. The table above shows how nutrient needs change for women during pregnancy and lactation, and is a quick guide to what the daily needs are for various nutrients.

A functional approach to SIBO management focuses on identifying the root cause of the overgrowth and creating an individualized plan. A tool commonly used in the functional medicine field is a comprehensive stool test to reveal more information about the digestive tract function.19 This tool focuses on biomarkers that provide information about digestion, absorption, inflammation, dysbiotic patterns, and intestinal immunology.19 Results of the stool tests also indicate if dysregulation of the immune system or digestive enzyme deficiency exists that fosters an environment for bacteria to grow.

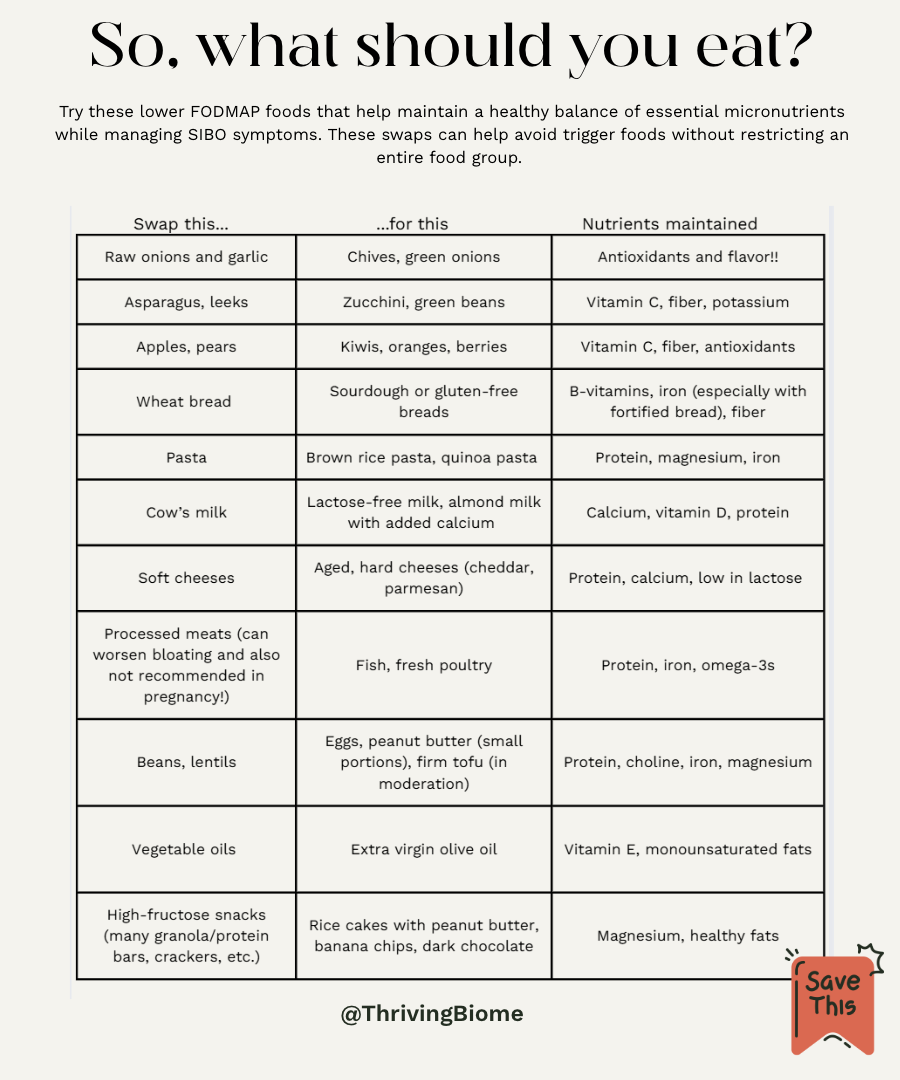

To treat SIBO and manage symptoms, avoidance of some foods is necessary, but a functional approach focuses on replacing higher FODMAP food items with quality foods that provide the same nutrients. Check out the chart to the right for some ideas about food swaps for common food items. Since the functional approach is more personalized, strict and extensive limitation and/or removal of food groups or foods may not be necessary. Working with a functional professional will allow room for individuals to approach SIBO management in a way that is best for them. The difference between the functional and conventional approach to a low FODMAP diet and food avoidance is how the underlying cause of SIBO is addressed. Conventionally, SIBO may be treated with the low FODMAP diet with little to no guidance about preventing nutritional deficiencies or by prescribing antibiotics to treat the overgrown bacteria. The most commonly recommended antibiotics prescribed are rifaxmin and neomycin or even a combination of the two. Rifaximin can be used to treat hydrogen positive SIBO, and is an oral dose taken three times a day for 14 days. 20 Intestinal Methanogen Overgrowth (IMO) is treated using a combination of rifaximin and neomycin.20 Rifaximin is administered the same as the hydrogen treatment and neomycin is taken twice daily for the same length of time.20 Not until two rounds of antibiotics have failed to improve symptoms is investigation into the root cause done in the conventional setting. Not only is this a temporary solution, but the underlying causes aren’t even considered until antibiotics are not effective two separate times.

In functional medicine, the root cause of SIBO is investigated and treated while food swaps and the indvidualized diet is being utilized. This approach targets the actual problem and finds a treatment that will create a gut environment that is not conducive to the overgrowing bacteria. For example, if chronic constipation is the root cause of SIBO development, treating the reduced motility will reduce the risks of SIBO returning while using food swaps or food avoidance to mitigate symptoms and ease discomfort. One functional treatment method is antimicrobial herb use that replaces antibiotic treatment and has been found to have the same effect as antibiotics.20 These antimicrobial herbs are less studied than antibiotics and should not be used when pregnant due to potentially extensive risks to the mother’s health and the development of the fetus. This method can be discussed with health professionals following the birth and completion of breastfeeding because of these potential risks. Additionally, the bioactive compound in garlic, allicin, can be used in treatment for methane-positive SIBO in combination with rifaximin or antimicrobial herbs as this compound is low FODMAP unlike garlic. This too should be considered only following birth and completion of breastfeeding to prevent harmful effects to both mother and baby.

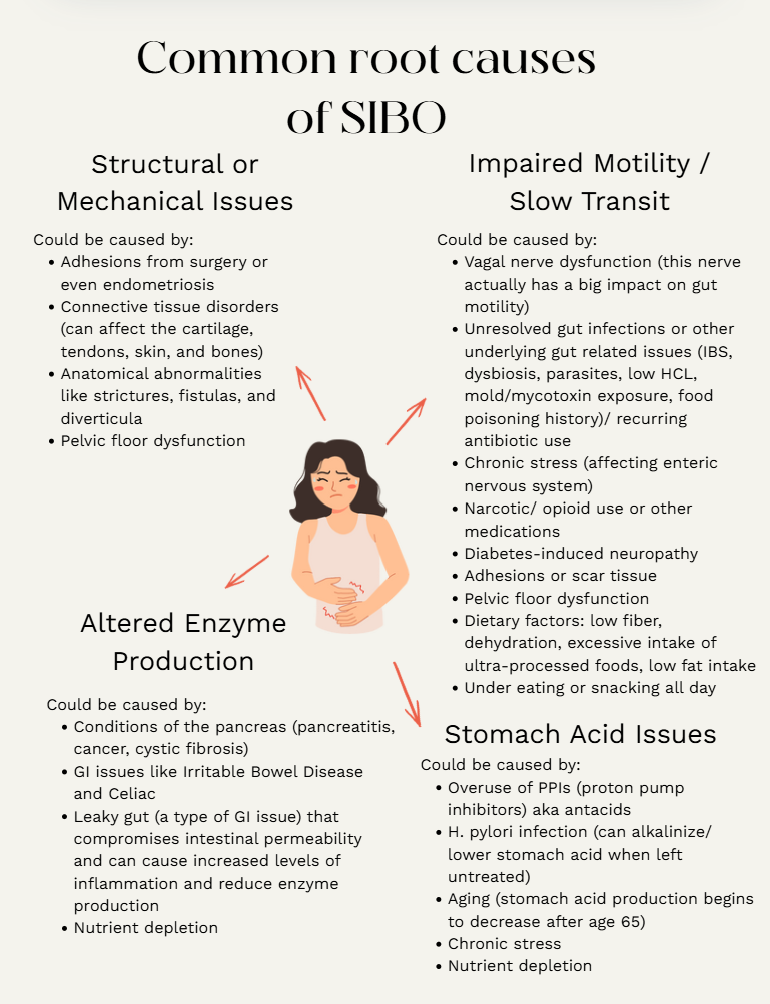

So, while the functional treatment methods include the low FODMAP diet, this diet is implemented in a controlled and individualized way that works against development of nutritional deficiencies. The main focus is on replacing the removed foods with equally nutrient dense options that prevent nutrient deficiencies and support the increased needs of pregnancy. While making these food swaps, there will be added attention to the root cause of SIBO. There are a number of possible root causes, including motility issues, anatomical abnormalities, diet, impaired immune function, and stomach acid production to name a few.21 The image below shows more examples of what may be causes of SIBO and what the root of that issue could be.

Motility issues can occur when food is not passed effectively or quickly enough through the digestive system, which allows bacteria to thrive.21 This can be caused by certain conditions that when addressed could relieve symptoms of SIBO and prevent regrowth of the non-beneficial bacteria. Anatomical abnormalities that can cause SIBO growth include strictures, fistulas, 21 diverticula, and other structural problems that may interfere with normal gut motility.21 A diet packed with sugar and carbohydrates feeds non-beneficial bacteria and can cause extra gas production.21 An immune function that is weak or functioning improperly is unable to prevent overgrowth of non-beneficial bacteria and may be unable to maintain the beneficial strains.21 Lastly, stomach acid impacts the type of bacteria that grows in the gut, so when there is decreased production of the stomach acid, non-beneficial bacteria can grow more easily.21 By addressing these root issues and creating an environment that does not promote non-beneficial bacterial growth will help prevent the return of SIBO.21

The functional approach works towards addressing these issues by utilizing the 5R Framework for SIBO. The 5R Framework is: Remove, Replace, Reinoculate, Repair, and Rebalance. 21 Triggers and stressors for the gut are eliminated from the diet or environment (in varying degrees depending on the individual and situation) in the Remove phase.21 Digestion and absorption are promoted via use of digestive secretion supplementation (enzymes and acids that are found in the digestive tract) to support nutrient utilization and uptake in the Replace phase.21 The Reinoculation phase focuses on foods and supplements that are packed with probiotics and prebiotics to help balance the microbiome.21 Repair of the gut, including the lining of the gut, is addressed through focus on nutrients like glutamin, zinc, and omega-3 fatty acids.21 This phase helps prevent an environment that is conducive to non-beneficial bacterial overgrowth. The last phase, Rebalance, addresses various lifestyle behaviors that can affect the gut, including sleep, exercise, stress, and hydration.21 These factors can alter gut function more intensely than many realize, which is why addressing them is so important in the healing process.21 When this approach to recovery is tailored to the individual, the process can be more effective.

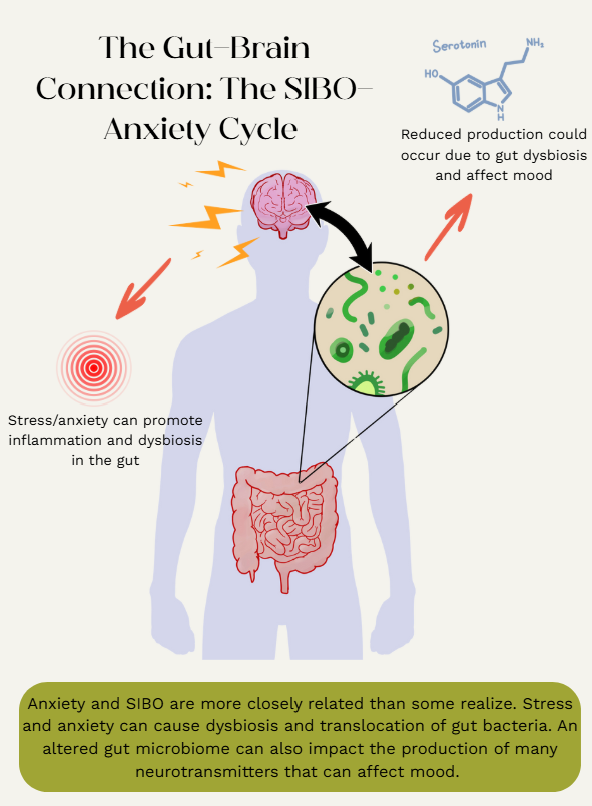

Research has shown that SIBO and anxiety are closely related and one can exacerbate the other. Some theories exist around why those with SIBO are more prone to anxiety and vice versa. Gut hormone production may be impacted by bacterial overgrowth in the gut, which in turn could negatively affect the gut-brain axis, a communication network that connects the enteric nervous system to the central nervous system in a bidirectional manner.22 Stress can cause dysbiosis and inflammation in the gut, which is often found in mental health disorders such as anxiety, depression, and autism.23 Stress can also cause extra movement of the gut bacteria, which can lead to bacterial overgrowth.23 This highlights why stress management is an essential step in overcoming SIBO and may be overlooked in conventional medicine settings. Microbes in the gut affect neurotransmitter function and production such as serotonin.22 This neurotransmitter is important for mood regulation and less serotonin availability can cause individuals with SIBO to be anxious.22 Diets that are less nutritionally dense, containing high amounts of refined carbohydrates and sugar, can negatively impact gut health and may be connected to reduced neurotransmitter levels in the body.22 Finding a diet that isn’t restrictive and reintroduces foods that were previously trigger foods can be intimidating, but knowing an individualized plan that prioritizes personal needs and symptoms is available makes managing and treating SIBO more achievable. Learning healthy ways to manage stress (yoga, meditation, adequate sleep, exercise, etc.) can have a greater impact on your gut health than most people think.22 So, when food reintroduction occurs, worrying about potential flare ups or triggering of symptoms could be exacerbating the problem. Feeling uneasy is totally understandable when you start reintroducing foods, especially after avoiding them for a while. Shifting your mindset from fear to curiosity can help regulate the nervous system and make the process feel more empowering. You’re also not alone in this! Community makes a difference. Whether online or in person, connecting with others who have gone through similar experiences can be incredibly supportive. If you’re looking for additional structure, support, and education about this process, check out Vital Side’s online course. Their program is designed to guide you from a state of fear to a state of calm and confidence through use of their courses that retrain the brain and support the nervous system.

The reintroduction phase of the FODMAP diet is often seen as the most challenging due to the fear of triggering symptoms and trying to follow a reintroduction schedule plan. This stage is only successful when done in a structured way that avoids confusing identification of potential trigger foods.24 Reintroduction of foods should follow a specific, set schedule that systematically increases the portion size for three days. For example, lactose can be reintroduced on the first day with 1/4C, the second day 1/2C, and the third day 1C. 24 If no symptoms are present, the low FODMAP diet is returned to for three consecutive days, called washout days, before moving on to the next food item.24 Then, when reintroducing other foods, keep lactose out of the diet to prevent making the process more complicated.24 If symptoms are present following reintroduction, wait until symptoms subside before halving the portion to test again.24 Another food from the FODMAP group can be tested to verify if results from the first food test were accurate (if milk was tried first, then try yogurt to verify results) or the next FODMAP group can be tested and it can be assumed that the previous group is a trigger (lactose for example).24 This schedule and process can be adjusted based on individual needs and conditions, making the pace faster or slower depending on sensitivity levels.24

As stated, the low FODMAP diet should not be followed long-term for more reasons than potential nutrient deficiencies. High FODMAP foods can be very beneficial to gut health and serve as prebiotics in the gut, especially fructans and galacto-oligosacchardies.24 These feed the beneficial bacteria in the gut, so removing all high FODMAP foods on a long-term basis can be counterintuitive to treating SIBO and reducing uncomfortable symptoms.24 To create a healthy, balanced gut microbiome, both high and low FODMAP foods are necessary. Also, the low FODMAP diet can feel very controlling because of the restrictions and limitations.24 Reintroducing and maintaining tolerable high FODMAP foods in the diet allows more control over your diet and enables you to manage your overall health more confidently.24

Take a moment and reflect on what you have read. Reread sections as needed and visit the sites linked in the blog for more detailed information on the topic. Hopefully, by the end of the post you feel like you have learned something valuable and ready to approach your SIBO diagnosis during this time of pregnancy with a better mindset.

Understanding where SIBO and nutrition come together during pregnancy can empower you to make confident, informed decisions for both you and your developing baby. Use the information to start thoughtful conversations with your healthcare provider, ask more specific questions, and explore a safer and more personalized approach to SIBO management without the harsh regulations of the typical low FODMAP diet. Ask about a more functional approach to treatment during pregnancy to avoid potential nutrient deficiencies and the use of antibiotics. Instead, focus on finding the root cause of SIBO and promote gut health with more optimal food choices. It is okay to question the methods of your current treatment plan, but remember, don’t try anything risky or make major dietary or supplement changes during pregnancy without professional guidance. Some of these strategies are better suited for after birth and once breastfeeding is completed. Making a change is possible, but always seek the guidance of a healthcare professional to ensure safe decisions are being made. You are your biggest advocate, trust your instincts, ask for support, and be confident knowing that a better and more personalized path is within reach.

References

1.Galon Veloso HM. FODMAP diet: What you need to know. Johns Hopkins Medicine. May 28, 2025. Accessed June 3, 2025. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/wellness-and-prevention/fodmap-diet-what-you-need-to-know.

2.Iacovou M. The low Fodmap Diet during pregnancy. Pregnancy and the low FODMAP diet - A blog by Monash FODMAP | The experts in IBS - Monash Fodmap. May 19, 2016. Accessed May 27, 2025. https://www.monashfodmap.com/blog/the-low-fodmap-diet-during-pregnancy/.

3.Dukowicz AC, Lacy BE, Levine GM. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: a comprehensive review. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2007;3(2):112-122.

4.Hydrogen, methane and hydrogen sulfide: Trio-SMART®. Trio-Smart. Accessed July 18, 2025. https://www.triosmartbreath.com/orderonline.

5.d'Afflitto M, Upadhyaya A, Green A, Peiris M. Association Between Sex Hormone Levels and Gut Microbiota Composition and Diversity-A Systematic Review. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2022;56(5):384-392. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000001676

6.Hill P, Muir JG, Gibson PR. Controversies and Recent Developments of the Low-FODMAP Diet. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2017;13(1):36-45.

7. Tian Z, Zhang X, Yao G, et al. Intestinal Flora and pregnancy complications: Current insights and future prospects. iMeta. 2024;3(2). doi:10.1002/imt2.167

8.Six key pregnancy hormones | American Scientist. American Scientist. Accessed June 26, 2025. https://www.americanscientist.org/article/six-key-pregnancy-hormones

9.Millard E. What’s really going on with your pregnancy hormones. BabyCenter. December 20, 2022. Accessed June 25, 2025. https://www.babycenter.com/pregnancy/health-and-safety/pregnancy-hormones_40010128

10.Mikami K, Takahashi H, Kimura M, et al. Influence of maternal bifidobacteria on the establishment of bifidobacteria colonizing the gut in infants. Pediatr Res. 2009;65(6):669-674. doi:10.1203/PDR.0b013e31819ed7a8

11.Gorczyca K, Obuchowska A, Kimber-Trojnar Ż, Wierzchowska-Opoka M, Leszczyńska-Gorzelak B. Changes in the Gut Microbiome and Pathologies in Pregnancy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(16):9961. doi:10.3390/ijerph19169961

12.Garcia de leon R, Hodges TE, Brown HK, Bodnar TS, Galea LAM. Inflammatory signalling during the perinatal period: Implications for short- and long-term disease risk. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2025;172:107245. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2024.107245

13.Mulak A, Taché Y. Sex hormones and the brain-gut-microbiota axis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;26(8):1057–1070.

14.Mor G, Cardenas I. The immune system in pregnancy: a unique complexity. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010;63(6):425–433.

15.Quigley EMM, et al. Gut microbiota and the role of enterobacteriaceae in SIBO. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2017;46(1):121–132.

16.Koren O, et al. Host remodeling of the gut microbiome and metabolic changes during pregnancy. Cell. 2012;150(3):470–480.

17.Uriu-Adams J, Daston GP. How Does Nutrition Influence Development? In: Teratology Primer. 3rd ed. ; 2018. Accessed July 15, 2025. https://www.birthdefectsresearch.org/primer/nutrition.asp.

18.King JC. Determinants of maternal zinc status during pregnancy. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2000;71(5). doi:10.1093/ajcn/71.5.1334s

19.Cloyd J. Dietary modifications for a successful SIBO treatment plan. Rupa Health. January 14, 2025. Accessed July 15, 2025. https://www.rupahealth.com/post/dietary-modifications-for-a-successful-sibo-treatment-plan.

20.Jankovic Weatherly B. What are the conventional and integrative treatments for Sibo? Bojana MD. September 25, 2021. Accessed July 18, 2025. https://drbojana.com/what-are-the-conventional-and-integrative-treatments-for-sibo/.

21.McGillis C. Understanding Sibo: A functional medicine approach. The Centre for Health Innovation. April 6, 2024. Accessed July 18, 2025. https://thechi.ca/understanding-sibo-a-functional-medicine-approach/#:~:text=Functional%20Medicine%27s%205R%20Approach%20to,elimination%20diets%20or%20targeted%20treatments.

22.Understanding the connection between SIBO and anxiety: What you need to know. Edinburgh Centre for Functional Medicine. May 22, 2024. Accessed July 18, 2025. https://edinburghcfm.co.uk/2024/05/22/understanding-the-connection-between-sibo-and-anxiety-what-you-need-to-know/.

23.Kossewska J, Bierlit K, Trajkovski V. Personality, Anxiety, and Stress in Patients with Small Intestine Bacterial Overgrowth Syndrome. The Polish Preliminary Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;20(1):93. Published 2022 Dec 21. doi:10.3390/ijerph20010093

24.Leech J. Fodmap reintroduction plan and challenge phase: Your simple guide and FAQ. Diet vs Disease. June 23, 2025. Accessed July 18, 2025. https://www.dietvsdisease.org/fodmap-reintroduction-challenge-plan/.